History

In 1943, North American Aviation developed the B-25H Mitchell as an improved follow-on to the B-25G. It carried the lighter 75 mm T13E1 cannon in place of the earlier 75 mm M4 gun, while also adding four forward-firing .50 caliber machine guns in the nose. Defensive armament was upgraded with a new tail turret and waist gun positions, features that became standard on both the H and J variants. Despite these advances, NAA sought to push the Mitchell further with a version designed for superior flight performance over all earlier models.

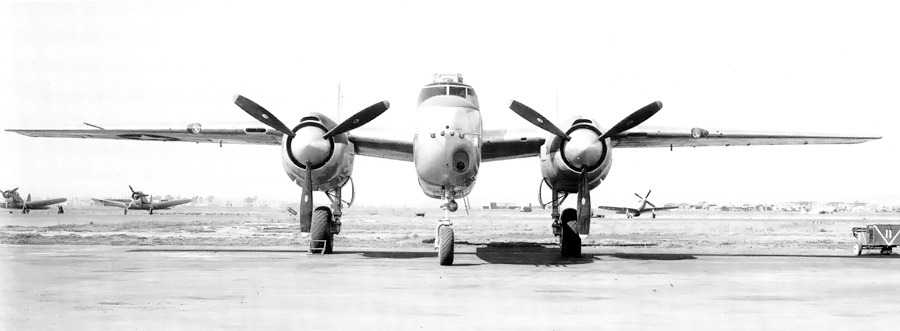

By early 1944, the company had drawn up the NA-98X, intended to extract the maximum performance possible from the B-25 platform. Among the promised improvements were new controls designed to reduce stick forces and a conventional single-tail in place of the B-25’s trademark twin fins. Power was to come from two Pratt & Whitney R-2800-51 air-cooled radials housed in low-drag cowlings, each rated at 2,000 horsepower with water injection for war emergency power. These were to be driven by four-bladed propellers with spinners. The wings were fitted with P-51–style tips and 12-inch longer balanced ailerons to improve roll control. A computing gun sight, a low-drag canopy for the top turret, a compensating sight for the tail guns, and illuminated reflector sights for the waist positions are also included. The 75 mm cannon of the B-25H would be retained.

The US Army approved the NA-98X proposal and authorized the conversion of an existing B-25H into a testbed. Because this was a private North American project and not a formal USAAF program, it never received an official Army designation. Instead, the company referred to it internally as the NA-98X, and it was nicknamed “Super Strafer” by NAA personnel. A single B-25H-5 (serial number 43-4406) was selected for modification, although two of the planned features, the single tail and four-bladed propellers, were never installed.

The completed test aircraft made its maiden flight on March 31, 1944. Behind the instrument panels, test pilot Joe Barton and flight engineer Jim Talman were manning the aircraft. The flight lasted one hour and yielded very promising results: reduced vibration, a higher roll rate, and significantly better performance than a standard B-25H. At war emergency power, 10,000 feet (3,048 m) was attained in 4 minutes and 54 seconds. Maximum speed was 328 mph (528 km/h) at sea level on war emergency power, while Barton later pushed it to 350 mph (563 km/h) at altitude. Compared to the B-25H’s top speed of just 273 mph (439 km/h) and climb rate of 790 fpm (4.0 m/s), these gains were dramatic.

The improved flight characteristics came largely from the powerful R-2800 engines, but they also introduced a problem: the testbed’s wings had not been strengthened to withstand the stresses of such high performance. NAA engineers warned pilots that the airframe could not handle dives at 400 mph (644 km/h) or abrupt high-g pullouts. To preserve structural integrity, the NA-98X was limited to a maximum of 340 mph (547 km/h) and a g-limit of 2.67g.

Over the following 25 days, NAA test pilots conducted 16 additional flights, confirming the aircraft’s superior handling and speed. Many involved in the program agreed this was what the B-25 could have been from the beginning, had the R-2800 engines been available in sufficient numbers.

Tragically, the project came to an end on April 24, 1944. Army test pilot Major Perry Ritchie, an experienced flier but known for his love of showy maneuvers, was assigned to evaluate the NA-98X. He had already been cautioned against abrupt pull-ups after high-speed passes, yet during his third flight in the aircraft, he repeated the maneuver. At an estimated 400 mph and an altitude of just 200 feet (60 m), he pulled up sharply, generating around 5g, well beyond the aircraft’s restricted limits. Both outer wing panels tore away, severing the entire tail assembly. The Mitchell briefly climbed another 300 feet (91 m) before spiraling into the ground, killing Major Ritchie and his copilot, First Lieutenant Winton Wey.

The crash completely destroyed the sole NA-98X. Investigation revealed a deep buckle on the upper surface of the right wing panel, but this was not considered the cause of failure; rather, it was the pilot’s decision to overstress the airframe. The investigation concluded that strengthening the wings could have prevented the disaster. However, the Army lost interest after the accident, and the project was permanently canceled.

In total, the NA-98X program lasted just 25 days. In total, the aircraft logged 40 hours of flight time, of which 21 hours were flown by North American pilots over 22 days. Major Ritchie logged the remaining 18 hours over three days.