- Oui!

- Non!

- Tech Tree Researchable

- Premium

- Squadron Researchable

- Battlepass Reward

- Event Rare

- Non!

Iéna is the pivotal battleship that cemented the French moving away from building tumblehome-deformed monstrosities That even the French Admiralty stated at times were “liable to capsize” into not just decent enough, but genuinely good capital ships… but only after the previous nine battleships were hampered by severe tonnage restrictions and constant government penny pinching.

With Iéna the French finally made a good 1st Class Battleship for the pre-dreadnought era… only to fall victim to time, in a way you might expect, and a way you certainly wouldn’t.

broadside of Iéna while on sea trials, 1902

directly bow and aft views of 1:250 model of Iéna- this thing is made of freaking paper and wood, but is incredibly well done and detailed, showing where even the smaller things are.

DESIGN:

As noted above, Iéna was the Marine Nationale’s 10th battleship of the steam-and-steel design era, following on from the deformed mutant semi-ironclad/semi-pre-dreadnought abomination of Brennus, then the only slightly somewhat less mutant members of the Flotte d’échantillons AKA Fleet of Samples; Charles Martel, Carnot, Jauréguiberry, Masséna, and Bouvet, and lastly the 3-strong Charlemagne-class which finally spurred a move away from extremely pronounced tumblehome hull designs, due to the issue of extremely pronounced tumblehome designs significantly magnifying the effects of flooding, in favor of a much more gentle tumblehome.

Iéna thus was designed as a general enlargement of the Charlemagne-class with a tonnage limit of 12,000 long tons (same as the older Flotte d’échantillons) but with much more experience in these limitations by this point, and not working off a design stemming directly (instead being 3 generations removed) from the French Frankenstein that was the poor old Brennus.

aside from the general look of a Charlemagne upscaled by 10%, the design specifications called for an armor scheme that could provide stability and buoyancy AFTER combat damage-induced flooding… AKA the bane of french battleships that suffered so much as a mean glare from the Germans that at this point were on the road to supplanting the French as the perennial number 2 naval power.

Iéna sported a top speed of 18.1 knots, a step up from the 17 of the previous design of the somewhat experimental but kind of redundant coastal defense battleship Henri IV. This was in contrast to a rather mediocre range of 4500 nautical miles, which didn’t really mean much as like the British, the French Colonial Empire spanned most of the world and there was always a coaling station in range if Iéna was ever sent to a far flung colony like Indochina… which it never was, sporting a spray on Mediterranean tan from start to end.

Iéna as it turns out, would excel in its design phase thanks significantly to director of naval construction Jules Thibaudier.

Thibaudier had the foresight to keep abreast of the latest developments in armor, with an earlier design calling for use of Harvey Steel (case hardened nickel steel), but modified from the original design to extend the height of the abovewater section of belt armor, AND THEN up the intermediate armament from the 138.6mm/45 Mle 1893 guns to the 164.7mm/45 Mle 1893/96 (not to be mistaken for the Mle 1893/96M). This revised design would be what Iéna would turn out as.

when in service, a particularly interesting characteristic of Iéna came to light- she rooooooooooooooolled… rather considerably apparently… but SLOOOOOOOWLY.

now while this sounds like a bad thing with Iéna being seemingly unstable, this in reality may have made Iéna about as perfect of a naval gunnery platform as a ship can get- and even the first ship captain Auguste-Georges Bouxin at the time stated in a late 1905 report: “From the sea-keeping point of view the Iéna is an excellent ship. Pitching and rolling movements are gentle and the ship rides the waves well.”

This shows that Iéna was both maneuverable (which is also supported by naval historians) and despite a heavy roll even after having bilge keels installed, this roll was so slow that all it really served was to slightly increase/decrease the main guns maximum range at the highest/lowest point of its roll.

With characteristics like these, it’s really no wonder Iéna is seen as the first genuinely good French battleship, not just passable or relatively decent in comparison to its peers and predecessors like the Bouvet or the Charlemagne-class, and even when considered as a pre-dreadnought in general.

HISTORY:

Life:

Iéna is named in reference to the twin battles of Jena-Auerstadt, which could probably be summed up as “the Battle of Austerlitz, of Prussia”… so continuing a habit that particularly the French and British had in the 19th century of naming things specifically after battles or captured ships where they had beaten the hell out of their enemies… A tradition of ye olde nationstate trolling I wish would come back.

Iéna was ordered on April 3rd, 1897 for construction at the Arsenal de Brest shipyards, laid down on January 15th, 1898, launched on September 1st, 1898, completed and commissioned on April 14th, 1902, at the final cost of just over 25 and a half million Francs, captained by Auguste-Georges Bouxin.

Iéna would have a rather inauspicious start to her career, with her first week after leaving Brest for Toulon resulting in a sailor going overboard and drowning, and a defective rudder making straight lines difficult on the way to Toulon.

upon arriving in Toulon, Iéna; being the newest battleship in the fleet; would immediately become flagship of the Second Division of the Mediterranean Squadron under Contre-Amiral (Rear Admiral) René-Julien Marquis, at the beginning of May. Throughout most of May Iéna would be docked and under repair likely due to the aforementioned rudder issues. Once the teething issues were fixed, Iéna would begin performing the singular task that comprised the vast majority of her career- port visits in southern France and French North Africa; presumably mainly Tunis, Algiers, and Mers-el-Kebir; for the entire second half of 1902.

In June 1903, Iéna would get its first working over by a head of state when during a full Mediterranean Squadron visit to Cartagena, Spain, King Alfonso XIII came to inspect the ship during the visit.

On November 3rd, 1903, René-Julien Marquis would be replaced as Iéna’s flagship admiral by Contre-Amiral Léon Barnaud… presumably as Marquis had just been promoted to Vice-Amiral.

Iéna would get its second and third dates back to back with heads of state during a fleet review off of Naples in mid-1904, where French president Émile Loubet and Italian king Vittorio Emmanuel III were both present. Iéna and the Mediterranean Squadron would then tour the northeastern Mediterranean along Ottoman and Greek islands and coastline.

1905 would be spend undergoing minor refits, port calls, and fleet movements, culminating in Contre-Amiral Léon Barnaud moving on to a larger role in the fleet, being replaced by Contre-Amiral Henri-Louis Manceron in November 1905.

1906 would be spent with Iéna and the Mediterranean Squadron assisting Naples after Mount Vesuvius erupted… unfortunately, they were about 1827 years too late to save the city of Pompeii to the northwest.

After this the Marine Nationale would start to conduct more major combined fleet maneuvers… likely because the Kaiserliche Marine was now larger than the Marine Nationale… Iéna now in its role as flagship of the Second Division of the Mediterranean Squadron, would conduct a joint exercise with the Second Division of the Northern Squadron, lead by the Coastal Defense Battleship Bouvines. After this there was a several months-long period of R&R, and participating in the Marseilles naval review in September 1906, a massive get-together of Royal Navy, Marine Nationale, Armada Española, and Regia Marina ships.

Soon after the review, Iéna would record the only confirmed kill of her career that wasn’t herself- a French 35-meter Type 1889 torpedo boat; No.96; when she accidentally rammed and sunk it, soon being warned that continuing to attack teammates would result in being returned to the hangar.

|

|

Death:

Iéna’s service came to a screeching end on the early morning of March 7th, 1907, when; while drydocked in Missiessy Basin at the major French port of Toulon for routine hull maintenance and deal with the chronically problematic propeller shaft; it suffered a catastrophic series of explosions due to spontaneous detonation of a 100mm shell inside the No.5 turret magazine due to deteriorated and unstable propellant. this initial explosion set off the rest of the magazine, with the flash detonation traveling to and setting off other magazines that quickly gutted the ship, nearly cut it in half, almost collapsed the entire aft superstructure, flattened the surrounding dockyard, and nearly capsized the nearby utterly cursed pre-dreadnought Suffren in the neighboring drydock, with a concussive wave that slammed the Suffren over to the side with nearly enough force to upend the ship.

|

|

Now this requires explaining as this kind of naval/maritime catastrophe is extremely rare and for the French, chiefly seen with the battleships Iéna and Liberté in this period- you see, the particular compound used as the smokeless powder propellant by France was the largely nitrocellulose-ether-paraffin based compound Poudre Blanche, the first ever brand of smokeless gunpowder originally developed, invented by chemist Paul Vielle in 1884. Over time this original formula would be improved, with Poudre BF(NT) in 1888, Poudre BF(AM) in 1896, and then Poudre BN3F in 1901 (this is as far as the story of Iéna goes, so later formulas are ignored).

Poudre BN3F was an especially important innovation as it replaced the use of amyl alcohol as the ether component with the antioxidant chemical diphenylamine, as the amyl alcohol component would degrade over time regardless of even pristine storage conditions and increasingly destabilize the compound, occasionally leading to drumroll please spontaneous combustion from heat buildup- an issue which France in particular had a rash of from the late 1890s up to about just before WWI; in addition to inconsistent firearms performance as the compound degraded.

|

Problem is, France had produced smokeless powder cartridges and artillery in factory mass production since 1886; so by this point there were BILLIONS of bullets and god knows how many millions of artillery shells across all calibers used by the army and navy in service. Meanwhile other nations adopted their own slightly later compounds like the American Dunnite (Explosive D), Austrian Ecrasite, or the Italian Ballistite, which mostly never had the issues of the more potent Poudre B or the British Lyddite (Cordite).

So the only real solution to removing the old and potentially long term dangerous Poudre BF(NT) and BF(AM)-propelled stock from the system was… well… use it. problem is that with higher calibers, there may be more or less stock going from 100mm to 305mm, but less likely it’s going to be used in a timely manner. So while in 1907 there were certainly some 305mm, 164mm, and 100mm shells carried by Iéna that did have the newer BN3F formula of Poudre B propellants, there absolutely was plenty of old stock across its 3 large cannon calibers, likely mostly featuring Poudre BF(AM).

|

|

And so, between 1:35-2:45 AM on March 7th, 1907, Iéna would briefly become the world’s largest self-sustaining hand grenade when it catastrophically detonated; repeatedly; killing 120 people across the skeleton crew inside, the dockworkers outside, and because of the tremendous explosion sending shrapnel so far and with such velocity; 2 random civilians in the Toulon suburb of Pont-Las, the most unlucky people in France that day.

|

During Iéna’s self-destruction, 3 of the ship’s workshops had their roofs blown clean off by the colossal explosions, the section of the ship between the rear funnel and rear main turret utterly gutted with the machinery (likely boilers) blown to pieces, and the explosion itself so powerful that not only did at least one side of the ship in this area have a blown out gash spanning from near the weather deck to the bottom of the belt armor, but that the upward force of the semi-contained explosion bulged the upper deck of the ship so badly that the resulting contraction then buckled the upper deck and caused the rear superstructure to slightly collapse inwards. miraculously neither of the main guns magazines detonated though somehow.

There were some people paying attention during the early morning meltdown however, as the République-class Pre-Dreadnought Patrie attempted to blow a hole in the drydock gate with one of Patrie’s main guns… but the shell bounced off. Soon after, one of Patrie’s crewmen, Enseigne de vaisseau Jean-Antoine Roux, got on to the dock and opened the drydock gate the traditional way… catching a fatal case of exploding battleship to the face for his efforts, apparently literally immediately afterwards.

Jean-Antoine Roux got a 2-ship class named after him though, the Enseigne Roux-class Destroyers of 1915. Not a bad showing all things considered.

|

|

Fate:

Unsurprisingly, the resulting investigation found Iéna to be a shattered wreck, with a minimum of 2 years and ~7 million francs required to bring it back into active service… in an environment where HMS Dreadnought was now running around and making waves… when it took 25.5 million francs and 4 years to build in the first place when it was a state of the art battleship halfway through the pre-dreadnought era… so it didn’t take long for the decision to just refloat Iéna and have it shot and sunk as a target.

|

|

Iéna was removed from navy inventory lists on March 18th and would officially be decommissioned from the Marine Nationale on July 7th, 1907. Across 1908 all useful (read: still usable) equipment save for the 305mm Mle 1893/96 main guns were removed, and the wreck repaired to the point of basic seaworthiness. Iéna was then moved and moored to a point off of the Île des Porquerolles.

Then in a move that i’m fairly sure was ENTIRELY coincidental, the target shooting of Iéna was conducted by the Gloire-class Armored Cruiser Condé firing 194mm AP shells propelled with an experimental new Melinite-based formulation of Poudre B as the smokeless powder compound- Melinite being a picric acid derivation and close relative of the British Lyddite and American Dunnite (Explosive D) formulas, and while the M in BF(AM) likely is Melinite, just about all development of picric-acid based smokeless powders going into the 1900s was less about making the powder more potent, and more about how to make it less terrifyingly volatile… or in the case of the Germans with their Fullpulver 88 smokeless powder, just ditching picric acid-based propellants altogether.

|

|

Many months and experimental AP shells later, on December 2nd, Iéna finally began to founder, necessitating a tow out to deeper water… which didn’t last long as the hazard of towing a sinking ship being that the ship under tow might sink before you get to where you want it to sink, which is what happened when Iéna finally sank in shallow waters.

The wreck would now be sold for scrap on December 21st, 1912… and not much else would happen as for whatever reason, it would take 3 salvage efforts all the way to 1957 to finally reclaim the now-ancient wreck of Iéna.

|

|

Post-death Investigation, Shenanigans, and Stupidity:

Now for the investigation itself, as despite being a shattered wreck in a Toulon drydock at this point, Iéna would continue to claim victims… and brain cells… in a hilariously drawn out series of investigations and scapegoating collectively known as the “l’Affaire des Poudres”

The investigation into the loss of such an important naval asset quickly …and correctly!.. established the cause of death: spontaneous detonation of a 100mm shell in the magazine feeding the number 5 100mm anti-torpedo boat gun, due to unstable Poudre B propellant spontaneously combusting due to the heat of an unattended and under-refrigerated room while in drydock. simple!

|

Aaaaaaand then everything went downhill from there.

Later in April 1907, what would be the main competing theory was published in a report that claimed that the explosion was actually from a torpedo going off in the torpedo room… which was right below the No.5 turret magazine room… am I the only one that thinks that may have been a somewhat questionable design choice?.. with the explosion pulverizing the shared ceiling/floor between the rooms and causing the chain reaction. As a result, a group called the Monis commission was put together to investigate the technical details; featuring mathematicians, chemists, and even Poudre B inventor Paul Vielle… which ended inconclusively, and further reinforced the blame on old and unstable Poudre B in a report dated July 9th. A second group; the Michel commission; was also set up, which only achieved the result of dragging the investigation and debates out to an even more hilariously pointless degree, to the point where it became quickly regarded as a complete waste of time.

And it was at this time, the wonderful spectacle that is the notoriously unstable, psychotic, and ruthless early 20th century French politics reared its ugly head, claiming Iéna’s final victim: Navy Minister Gaston Thomson, who had absolutely nothing to do with Iéna, but who was labeled as grossly negligent and forced to resign soon after… because apparently they had to have SOMEBODY to blame.

In all, it was a rather ugly and unfitting way for a genuinely important French battleship to go down, self-destructing 15 years before it likely would’ve been decommissioned, and of course missing WWI.

GENERAL CHARACTERISTICS:

Displacement:

11,688-11,860 metric tons at normal loads (11,503 long tons)

12,105 metric tons fully loaded (11,914 long tons)

Length:

122.3-122.4 meters overall (normal and full loads)

122.2 meters at the waterline

Beam:

20.81 meters

Draft:

8.38 meters

Engines:

the powerplant was 20 coal-fired Belleville boilers feeding into 3 VTE steam engines connected to 3 shafts connecting to 3 propellers, the outside two of which were 4.5 meters in diameter while the inside prop was 4.4 meters in diameter, for an estimated 16,500 metric horsepower (16,274 ihp) for a speed of 18 knots (33 km/h; 21 mph); but in service turned out to be almost exactly correct, in sea trials showing an actual result of 16,590 mhp (16,362 ihp) for a top speed of 18.1 knots (33.5 km/h; 20.8 mph)

Fuel:

1080 tons of coal

Endurance:

4,400 nautical miles at 10.3 knots

Crew:

as flagship with admiral onboard (vast majority of active service): 48 officers, 731 enlisted

as normal: 33 officers, 668 enlisted.

ARMOR:

hull construction is of mild steel AKA Constructional Steel

armor material used is Harvey Steel (face-hardened nickel steel) unless specified otherwise

Iena had a complete belt spanning from stem to stern,

detail drawing of Iéna, including (if not highlighted) armor profile

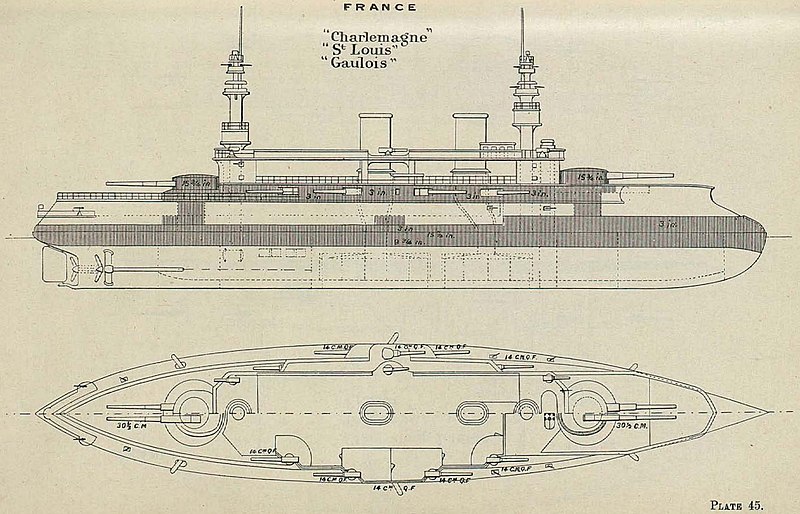

armor profile of the Charlemagne-class, the ships that Iena is largely a 10% upscale of, and shares a highly similar belt layout, if not thickness

The upper armor belt above the main sections was made of two strakes in the area where the hull sloped inwards to form the tumblehome below the lower portholes. - in addition to the detail drawing, across the various pictures of the 1:250 model of Iéna, you can see this in the areas where these are in 3D in the discolored areas about the red waterline paint.

the upper strake was 80mm thick, and the lower strake 120mm thick. the height of the upper belt (see Iena drawing above, and compare against Charlemagne-class profile) for the majority of the ship amidships was 2 meters, with the upper belt stepping down from the area of the stern to about 1/5th of the way across the rear of the ship; and conversely the upper belt extending upwards a bit (including about 9 portholes) for roughly a quarter of the ship to the bow.

|

|

Main Belt:

so with the main belt, its seems to be a 50/50 split as to the figures of part of the belt, so i’m going to mention both with a forward slash to differentiate-

Navypedia and Conway’s are the main sources of the former figures, and Wikipedias (via their sources) are the source of the latter figures

Iéna had a complete waterline belt of Harvey armor that was 2.4 meters tall- 0.9 meters above the waterline, 1.5 below.

the main belt was 330mm(NC)/320mm(Wiki) thick for a length of 83.9 meters (so 84 meters),

after which the belt thinned to 230mm(NC)/272mm(Wiki) on the forwards section all the way to the bow, and 230mm(NC)/224mm(Wiki) on the aft section all the way to the stern.

at the bottom edge of the belt, the thickness tapered to 120mm(NC)/120mm(Wiki), with the bottom armor plates of the stern section being even thinner at 100mm according to only the wiki

Additionally, the lower strake down to the thinner bottom was further backed to protect against flooding, with a significantly subdivided cofferdam filled in all over with thousands of bricks of compressed zostera seaweed. apparently this seaweed would expand upon contact and plug any shell holes, like a turn of the century version of expanding foam.

|

|

Armored and Splinter Decks: (the deck below the open air weather deck, and the deck below that)

the armored deck is something to behold for its time- a cellular layering of a 65mm hardened steel plate backed below by two stacked 9mm plates. below all this was an additional splinter deck to catch anything that made it through the armored deck, with the floor of the splinter deck being itself a stack of two 17mm plates

in all, this was a pretty impressive level of armor for the deck for the time, with 83mm of protection across the armor deck minus effective protection from the unbonded backing plates and plus effective protection from the hardened steel, followed up with 34mms a deck down to absorb low-pen Common shells for ~117mm of combined protection across 2 decks.

|

|

Casemates:

The 164mm central battery casemate gun rooms had 90mm armored walls enclosing the rooms, while the gun shield for the 164mm gun was itself armored 70mm thick all around.

Additionally the 164mm guns maintained a small ready rack supply of ammo from tubes moving the ammo from their respective magazines to the casemate room, and these tubes were armored to an impressive 200mm thick.

|

|

Main Guns and Barbettes:

the oval-shape turrets were 290mm thick all around due to being a one-piece monolithic turret.

the roofs of these two turrets were 50mm thick, and only made of mild steel, the same material as the regular hull of the ship.

the main gun barbettes were 250mm thick all around

|

|

Transverse Bulkhead:

It seems Iéna only had a forwards transverse bulkhead, and lacked a rear one (as so far i cannot find any reference to one), meaning it does not technically have a citadel if this is the case, though having a full length belt somewhat mitigates this.

the transverse bulkhead spanned from the top of the central battery area, specifically to protect it (the 164mm casemate gun rooms and most of the base of the superstructure) down to the top of the armored deck, starting at a thickness of 150mm, and thinning to just 55mm at the connection with the main armored deck plate.

so not only is there seemingly no citadel, a protection methodology that came about when wooden warships were still considered modern, but the one end of what would be part of the citadel that is present is both high up in the ship, and just protects the base of the front of the superstructure and sponge any shell fragment that bounce off the armored deck.

|

|

Conning Tower:

the conning tower was practically the best protected place of the ship, as befitting the area almost nobody in any navy ever used.

front: 298mm

rear: 258mm

|

|

communications tube:

200mm

ARMAMENT:

like all Pre-Dreadnoughts, Iéna has an excessive array of calibers, though surprisingly forgoing a couple of calibers, making logistics far easier… by pre-dreadnought standards… as well as spotting the main 12-inch guns shell splashes less of a hassle.

2 x 2 - 305/40 Canon de 305mm Modèle 1893/96

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Canon_de_305_mm_Modèle_1893/96_gun

http://www.navweaps.com/Weapons/WNFR_12-40_m1893.php

aft main guns of Iéna, March 1907, immediately (maybe the next day) after most of the rest of the ship was wrecked by practically every other calibers propellant charges self-destructing.

This was the pinnacle of French capital ship main gun development in the pre-dreadnought era, first seen on the Charlemagne-class pre-dreadnought Gaulois, going through to the final French pre-dreadnought class, the Liberté-class.

these were mounted in twin turrets that had the entirety of their machinery built inside the turret, as barbettes were not yet really a thing at the time of their design.

they had a vertical traverse of −5° and +15°, were manually elevated/depressed, and after firing, and needed to be fully depressed to −5° in order to reload- which is why its fire rate was a rather poor ~1 RPM.

the muzzle velocity was roughly 2,674 fps (815 m/s)

These guns had a range of ~12,000 metres (13,000 yd) at the maximum elevation of +15°.

The magazines stored 45 shells per gun, and an additional 14 projectiles were stowed in each turret for ready use- though with how slow the guns fired, it really doesn’t matter how slow the ammo hoists replenished ready use stock, so there’s no point at which the 1893/96 would ever slow its fire rate.

|

|

8 x 1 - 164.7mm/45 Canon de 164mm Modèle 1893/96

http://www.navweaps.com/Weapons/WNFR_65-45_m1893.php

the main intermediate guns were the 164.7mm 45-caliber Mle 1893/96- specifically the original modification of 1893/96, not the 1893/96M.

they were mounted in a central casemate battery on the upper deck in traversable gun shields (so basically sponsons), one of the few times where casemate guns were legitimately useful where they were placed- the picture below is from them for a railway mount, and is a good sight of what the guns look like from behind, even if the gun shield here is likely totally different.

1:250 model of Iéna, with the locations of the 164mm guns very clear in their placement.

At their maximum elevation of +15°, their muzzle velocity of 800 m/s (2,600 ft/s) gave them a maximum range of 9,000 metres (9,800 yd).

Each gun was provided with 200 rounds, enough for 80 minutes at their sustained rate of fire of 2–3 rounds per minute.

|

|

8 x 1 - 100mm/45 M1893

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Canon_de_100_mm_Modèle_1891#Naval_Use - the L/45 1891, 1893, 1897, and 1917 versions are all largely the same, with slight constructional differences (none in mechanics or shell performance)

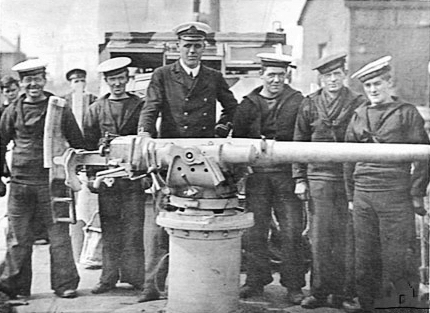

one of the this pattern of 100mm gun, aboard Bulgarian torpedo gunboat Nadezhda at some point between 1900 and 1912. at least the Bulgarians bothered to give it a friggin’ gunshield.![]()

These guns fired a 14 kilo shell at ~710-740 m/s (2300-2400 ft/s), which could be elevated to 20° for a maximum range of 9,500 meters.

Their theoretical maximum rate of fire was six rounds per minute (10s reload), but only three rounds per minute (20s reload) could be sustained, possibly for the same reasons as the 47mm guns- lack of ready use storage and slow ammo hoists.

100mm ammo count was 240 shells for each gun, fed from their respective magazines.

the secondary anti-ship guns were the 100mm L/45 Mle 1893, placed on open mounts on the shelter deck (open air, under cover), with 2 on each side directly above the 164mm casemate guns, above and behind the bow main gun turrets on the superstructure, and the same area behind the aft main gun turret on the rear superstructure platform, as seen below:

1:250 scale model of Iéna from starboard bow, and port aft, though hard to see as they’re painted the same beige as the model the 100mm guns are clearly visible

|

|

20 x 1 - 47mm/40 Canon de 47mm Modèle 1885 Hotchkiss (Hotchkiss 3-pounder)

http://www.navweaps.com/Weapons/WNBR_3pounder_H_mk1.php

QF 3-pounder Hotchkiss - Wikipedia - the 40-caliber short barrel French 3-pounders were largely identical to their British counterparts

overhead view of Iéna 1:250 model, showing i think 14 of the 20 Hotchkiss 3-pounders

the main torpedo boat defence consisted of twenty of the venerable Hotchkiss 3-pounders, fitted at just about any point they could be placed, with some in platforms on both military masts, embrasures (mini-casemates) in the hull, and in the superstructure.

The ship’s magazines held 750 47mm shells for each gun (15,000 total), with apparently nowhere near enough ammo stored for ready use near the guns themselves.

Their theoretical maximum rate of fire was fifteen rounds per minute (4.0s reload), but only seven rounds per minute (8.57s reload) sustained- so once the ready rack is exhausted and its resupply goes straight to the gun itself.

this issue of slow reloading for such a light shell was such that in 1903, Contre-amiral René Marquis criticized how the 47mm guns were utilized in service, stating in a 1903 report that the amount of ready use ammo was insufficient for the guns needs (repeated suppressive fire against torpedo boats) and the ammo hoists being “desperately slow”… all for shells weighing a kilo and a half… at a time when 3-pounder guns were just about useless as point defense, astorpedo boats were now approaching the size that 76mm 12-pounders were nearing the edge of viability

|

|

4 450mm Mle 1889 torpedoes (2 submerged at the beam, 2 in mounts)

Iéna carried four 450mm torpedo tubes, two on each broadside, one submerged and the other above water in a traversable mount.

The submerged tubes were fixed at a 60° angle from the centerline and the above-water mounts could traverse 80°.

8 live Mlè 1889 torpedoes were carried for one reload per tube.

SOURCES:

online:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/French_battleship_Iéna

https://ru.wikipedia.org/wiki/Йена_(броненосец)

https://www.navypedia.org/ships/france/fr_bb_iena.htm

http://www.modelshipgallery.com/gallery/bb/fr/iena-250-mm/mm-index.html - this is a site detailing a very quite well done 1:250 scale card/paper/wood model of Iéna

http://dawlishchronicles.blogspot.com/2016/04/the-iena-and-liberte-disasters-1907-and.html - mostly about the explosions of Iena and Liberte

literary:

Conway’s All the World’s Fighting Ships, PDF page 304

Caresse, Philippe (2007). “The Iéna Disaster, 1907”. In Jordan, John (ed.). Warship 2007. London: Conway. pp. 121–138. ISBN 978-1-84486-041-8.

Gille, Eric (1999). Cent ans de cuirassés français [A Century of French Battleships] (in French). Nantes: Marines édition. ISBN 2-909-675-50-5.

Silverstone, Paul H. (1984). Directory of the World’s Capital Ships. New York: Hippocrene Books. ISBN 0-88254-979-0.

Caresse, Philippe (2018). “The Battleship Iéna”. In Taylor, Bruce (ed.). The World of the Battleship: The Lives and Careers of Twenty-One Capital Ships of the World’s Navies, 1880–1990. Barnsley: Seaforth Publishing. ISBN 978-0-87021-906-1.

Балакин С. Последние броненосцы Франции // Моделист-Конструктор. — 1993. — № 7. — С. 31—32.

Якимович Д. Б. Эскадренный броненосец «Йена». — М., 2013. — (Морская коллекция № 10 (169)). — 1050 экз.

.jpg/800px-%D0%AD%D0%BA%D0%B8%D0%BF%D0%B0%D0%B6_%D0%B1%D0%BE%D0%BB%D0%B3%D0%B0%D1%80%D1%81%D0%BA%D0%BE%D0%B3%D0%BE_%D0%BA%D1%80%D0%B5%D0%B9%D1%81%D0%B5%D1%80%D0%B0_%D0%9D%D0%B0%D0%B4%D0%B5%D0%B6%D0%B4%D0%B0(2).jpg)