- Yes!

- No!

- as a standard tech tree ship!

- As a Premium!

- As a Squadron Researchable!

- As an event rare! For the Memes!

- No!

This is a suggestion for an armored cruiser that made for a major paradigm change when it was launched. a product of the innovative thinking of it’s doctrinal sponsor Jeune Ecole, yet completely unlike the Jeune Ecole in NOT hamstringing the Marine Nationale, This is the Armored Cruiser Dupuy de Lôme, a cruiser so far ahead of its time, it showed its contemporaries to be well past their time.

laid down in 1888, launched in 1890, and commissioned in 1895; the Dupuy de Lôme was the first Armored Cruiser in French service, and the first major evolutionary development of the concept of Heavy Armored Cruiser; from the ironclad era paradigm of a poor man’s battleship for second rate nations unable to afford a proper 1st or 2nd class battleship… or if the Brits found a few quid hidden in the couch…; into the first recognizable ancestor of what would later become the Heavy Cruiser.

this suggestion is specific to the Dupuy de Lôme as it was as of late October 1897 to 1902, as it’s 1895-1897 incarnation was only slightly modified for a great improvement, along with obsolete cast iron ammunition being removed. Meanwhile the post-1902 refit was uniformly worse afterwards.

|

|

Dupuy de Lôme at opening of the Kiel canal, 1895; note the extended spur bow, a type of cut-away or inverted bow

_(Kiel_71.172).jpg)

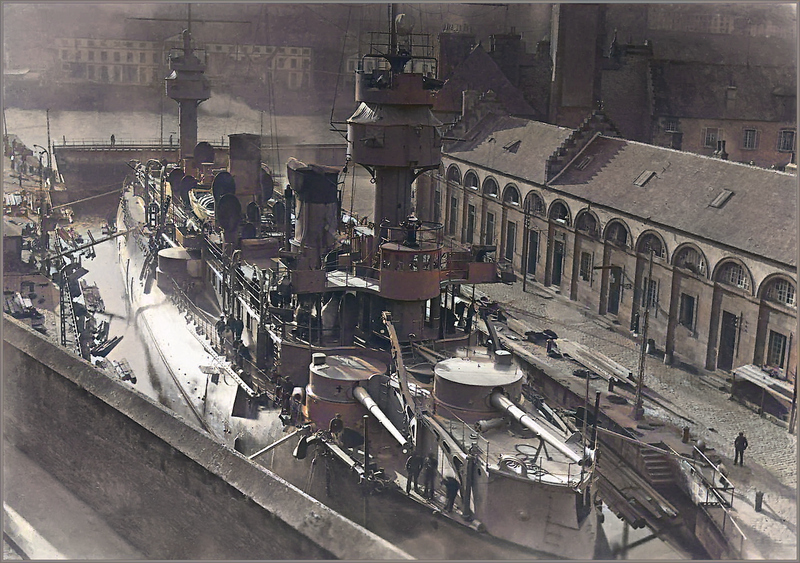

Dupuy de Lôme at drydock, sometime prior to 1902, colorized with Playback-fm

“Actual livery of the cruiser before refit. Black hull, copper acetoarceniat green under the waterline, canvas beige for the superstructure. It was painted standard overall grey afterwards and the hull was probably repainted in modern red.”

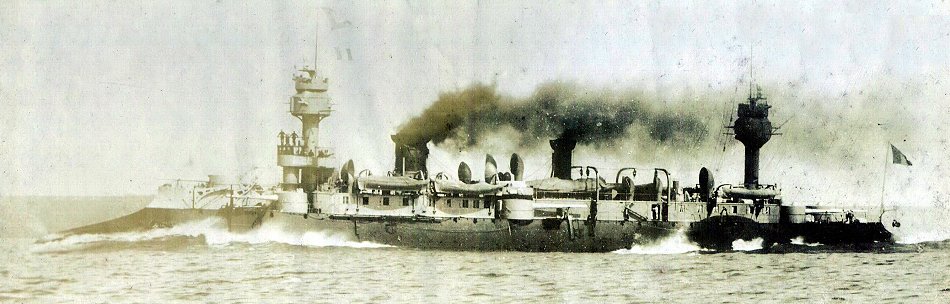

Dupuy de Lôme at sea at some point prior to 1902

DESIGN:

the Dupuy de Lôme was the first Armored Cruiser designed as part of the Jeune École naval doctrine, and in spite of the dramatic failings of the Jeune École, this particular development from it would prove to be the way forwards for all Armored/Heavy Cruisers up until the concept of the gun cruiser itself was rendered obsolete in the early Cold War environment.

The Jeune École Doctrine that spawned this ship was a novel and optimistic (read: deeply flawed and shortsighted) doctrine embraced by the French in the 1880s as a counter to the traditional style of battlefleet epitomized by the British Royal Navy.

Achieved through the use of speedy commerce raiders of all (small) sizes from the contre-torpilleur (Torpedo Boat Destroyer, and later just Destroyer) to submarines- France summarily being the first nation as of 1900 to be fielding an effective (if very short range) submarine force; as well as high speed cruiser designs specialized for commerce raiding- but at the doctrinal cost of no new true battleships built for almost a decade, instead fielding the occasional Armored Cruiser classes built more to backstop the contre-torpilleurs in the event of war with anyone serious like the Russian or British empires… meaning the British Empire.

|

|

As the Jeune École peaked and then began to loosen its stranglehold on Marine Nationale thinking going into the naval design era of Steam-and-Steel in the 1890s, work would be restarted on larger cruiser and capital ship developments; with a previously partially cancelled Charles Martel-class ironclad battleship reworked into an unstable, frankenstein, ersatz, semi-Ironclad / Semi-Pre-Dreadnought Battleship named Brennus… and oh boy was that a disaster.

But with the restarted development of Armored Cruisers blossoming into something truly special- the Dupuy de Lôme.

|

|

you see. during the majority of the era of Steam-and-Iron, Armored Cruisers were something of a semi-workable oxymoron- Cruisers usually needed to be of average or above-average speeds for the time but have relatively high endurance to traverse and… you know… CRUISE… the vast territories of empires like Britain, France, Russia, and (at least still at this point in time) Spain. but the thick slabs of iron needed to be effective in combat would greatly weigh them down, slow them down, and drive up costs to the point where there could be pressure to just pay an extra amount and get a full battleship out of it- resulting in the technological dead end design of Unprotected Cruisers, and thanks to Elswick in the 1880s; the much more robust Protected Cruisers; which had armor only on the decks to protect against plunging fire in a time where black powder muzzle velocities gave artillery a rainbow like firing angle, and maintaining no expensive armored waterline belt to handle a close range battle.

What was then called the Heavy Armored Cruiser would remain something of a niche really favored only by the Russian Empire and its awkward distribution of usually frozen over coastlines and limited finances; as well as rising minor and fading major nations that couldn’t/wouldn’t foot the bill for full battleships- like the United States as seen with USS Maine, (ACR-1), or Spain with the Infanta Maria Teresa-class… and of course eventually the British too because 1: Money. 2: ALL OF THE MONEY. and 3: the entire ironclad era for the Royal Navy was basically just kind of an anything goes open testing period, with this era’s armored cruiser lineage culminating with the Orlando-class Cruiser of 1886.

But then France began development of an Armored Cruiser at the end of the 1880s- the Dupuy de Lôme. unlike contemporary armored cruisers whose speed was more in the 14-17 knot range and capped out at 18 knots at the absolute most and only for very short periods at forced draft (overpressured boilers), Dupuy de Lôme sped along at nearly 20 knots- even while using subpar machinery in the goofy arraignment of one vertical triple expansion reciprocating piston steam engine, and two horizontal triple expansion engines, all fed by highly suspect boilers that had to be replaced despite being brand new.

another major difference from predecessors was its combat potential- previous and even parallel contemporary armored cruisers would have an armor scheme with an incredibly thick armored belt of 10-12 inches (254-305mm) thickness that could stop just about anything reasonable shot at it. the massive problem with this on-paper stats juggernaut was the actual surface area of this belt.

|

|

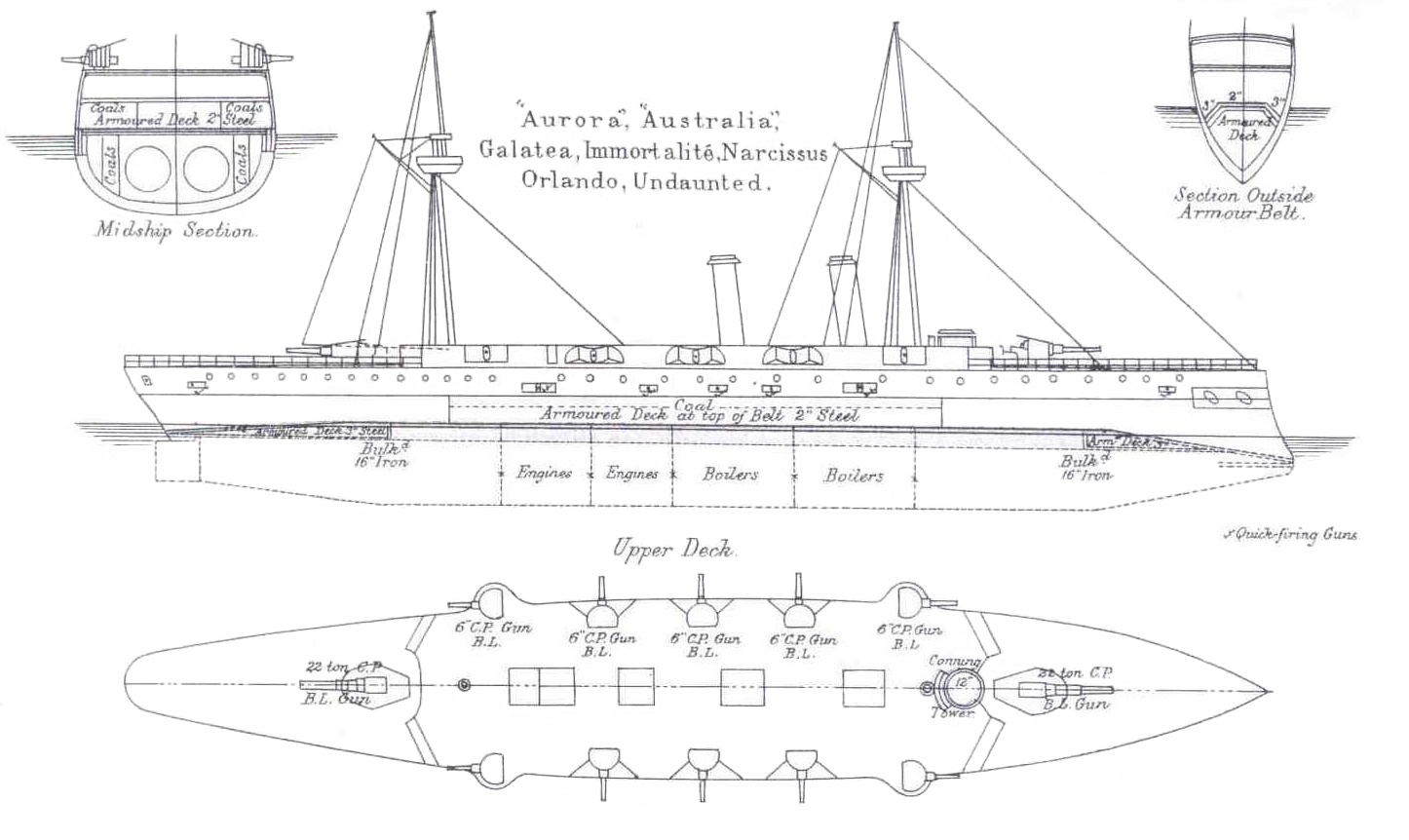

as seen in the below cross sections… it would be more impressive if you actually DID hit the belt armor, even under practice conditions!

Orlando-class cross section, Brassey’s Naval Annual 1888

Infanta Maria Teresa-class cross section, Brassey’s Naval Annual 1896

these belts were so short and stout that these ships were in all practicality completely unarmored above the waterline. These armored cruisers were built in the style of being like diminutive pocket battleships… unfortunately the kind of battleship they were the GT Sport Edition of was the Italia-class Ironclad… FYI that’s the Italian battleship class that had no ****ing armor, only some hopes and prayers.

Dupuy de Lôme on the other hand went for the opposite paradigm- a mere 100mm (4 inches being 102mm) of belt armor… but across the entire side of the ship from below the waterline right up to the quarterdeck, never thinning at any point along its span.

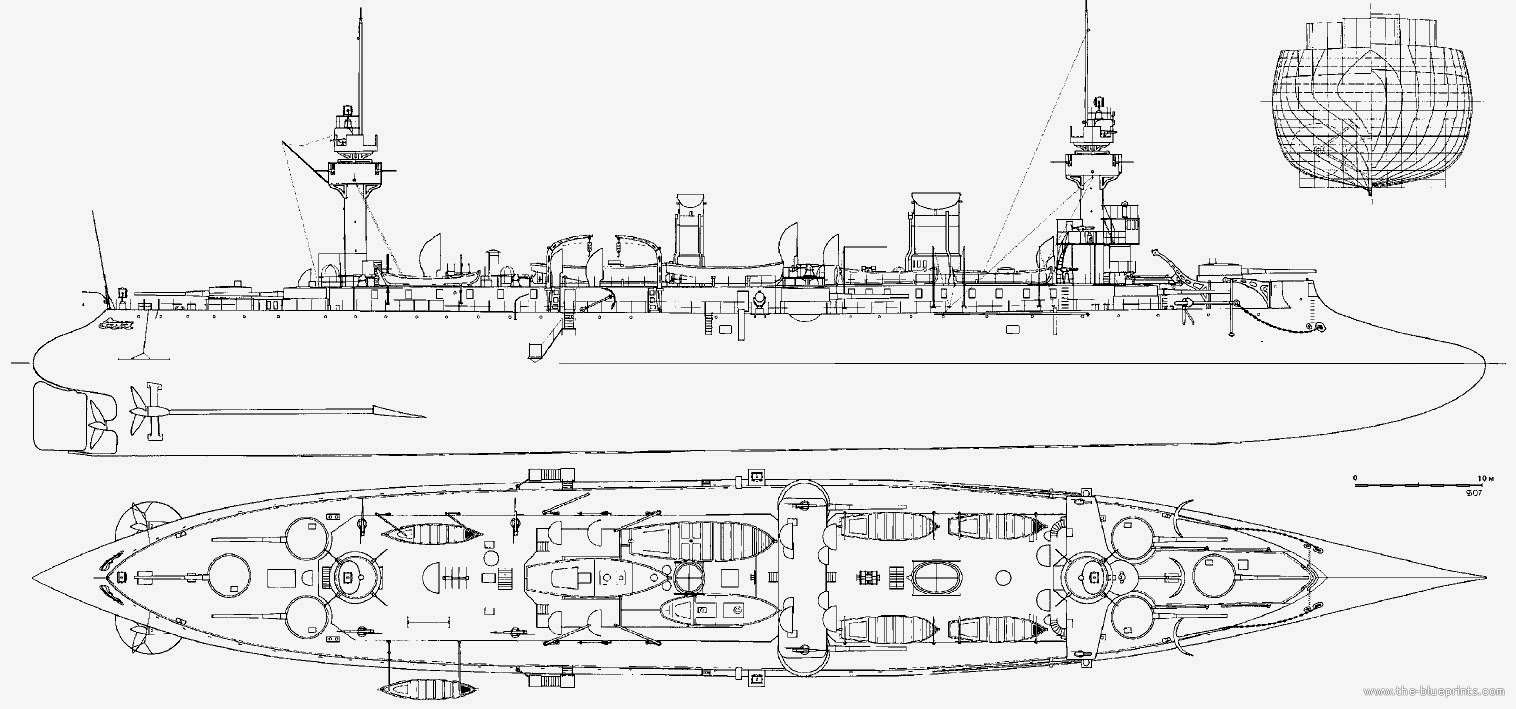

Rough sketch of the French armoured cruiser Dupuy de Lôme, from Brassey’s Naval Annual 1902

Another key difference from the old style of armored cruiser shown by Dupuy de Lôme was its armament (quirky French gun placement notwithstanding).

unlike the older last-generation design armored cruisers which were modeled as scaled down battleships with the main armament in turrets and the secondaries in casemates, Dupuy de Lôme had all its heavy armament in turrets, making the ship more flexible in combat as well as maximizing end-on fire. and speaking of its heavy armament- these were some of the first long barrel (and not ludicrously large) naval guns in service with anyone, with both the 194mm and 164mm guns having L/45 caliber barrels, allowing for muzzle velocities in the 770-800s m/s range at the same time most others couldn’t reach 700 m/s yet, or even further down the line when propellant charges switched from black or brown powders to smokeless.

SERVICE HISTORY:

Dupuy de Lôme was laid down at the Brest Shipyards on July 4th, 1888; launched on October 27th, 1890; commissioned on May 15th, 1895, and decommissioned on March 10th, 1910; though that wouldn’t be the end of her lifetime.

During construction, Dupuy de Lôme suffered from the teething issues of an entire industry, as early nickel-steel armor plates made by Le Creusot were frequently defective… plates which were largely accepted anyway. This is when the world was going from the well known sturdy but brittle ultra-low carbon content steel to a brand new ultra-high carbon content and also nickel-alloyed steel.

When Dupuy de Lôme went on her initial sea trials on April 1st, 1892, the questionable integrity of the powerplant made itself known when a boiler tube exploded, somehow managing to only non-fatally broil 16 sailors.

replacing these boilers with less homicidal ones took a year, and the eventual October 1893 sea trials showed that; now with working boilers; the engines themselves were both structurally unsound and borderline dangerous… and they also massively underperformed, producing a few thousand less metric horsepower than called for, and ALSO required a full replacement.

|

|

yeah that’s not a good sign when both halves of your cutting edge powerplant design need a full replacement before even commissioning into service.

|

|

even more eventually, Dupuy de Lôme tried for third times the charm in November 1894, which proved… ehh, good enough, as while the new engines still just slightly underperformed, that underperformance produced 2 knots consistently over a 24-hour period, more than any other armored warship could attain for maybe a few hours at peak performance.

Dupuy de Lôme was finally, FINALLY commissioned into the Marine Nationale on May 15th, 1895, assigned to the Northern Squadron, and destined for a very peaceful life.

Dupuy de Lôme’s first couple years was spent more as a giant yacht than a warship- the Kiel Canal opening, Tsar Nicholas II of Russia showing up at Cherbourg, French President Félix Faure, and visits to Spain and Russia. in October of 1897 Dupuy de Lôme was updated to the form (1897-1902) actually being suggested- Bilge Keels, in order to halve her roll and roll rate.

Years later Dupuy de Lôme would visit Portugal and Spain in June 1899, and a couple more years later would be present; as was everybody and everything else; in Spithead in early 1901 for the funeral of the deceased Queen Victoria.

Dupuy de Lôme would begin the final leg of its service life in 1902, when it was recalled to Brest for a massive overhaul that would span for 4 years. the vast majority of this overhaul was the complete replacement of the powerplant, with the old and ever unreliable fire tube boilers replaced with 20 brand new Guyot-du-Temple water-tube boilers, that additionally required the fitting of a third funnel and accompanying structure modifications and reinforcements alongside the rear mast being replaced with a far simpler pole mast.

all this change resulted in ~200 less horsepower… and a knot and a half less of speed at 18.27 knots- entirely defeating the purpose of Dupuy de Lôme… in 1906.

she could now be reliably outpaced by the 2nd generation of post-1900 pre-dreadnoughts, let alone be run down and massacred by newer protected cruisers, the first light cruisers, various armored cruisers, and the brand new iconic battleship HMS Dreadnought.

as if instantly realizing that this was a massive waste of money, Dupuy de Lôme came out of the dockyard in October 1906, and straight into reserve for 23 months. She was recommissioned in September 1908, bound for Morocco- one of the pre-WWI potential flashpoints between France and Germany. this lasted all of however long it took to realize that the ship was rusting on the outside, and the water plant was rotting on the inside, necessitating a return to the drydock in 1909 for a dismantling and deep cleaning.

Once she had drinkable water again… the party was over. Dupuy de Lôme would be deemed uneconomical to further repair, placed into reserve, and officially decommissioned from Marine Nationale service on March 20th, 1910, though not actually being removed from navy inventory lists until February 20th, 1911.

total service lifetime: 15 years, 9 months, 5 days.

|

|

But this was not the end. there were still quite some misadventures to come.

Due to rumors of Ecuador buying the Italian protected cruiser Umbria, Peru offered to buy the Dupuy de Lôme for 3 million francs in installments plus the cost of repairs prior to handover. These repairs were done by March 6th, 1912, with the ship being formally renamed Commandante Aguirre… and then Haiti of all places bought the Umbria, Causing the Peruvians to cut their losses.

The now-again Dupuy de Lôme would just kind of sit for 3 years, with consideration for modernizing being quickly dropped due to her extreme obsolete status… and so she sat in port for the entirety of World War One.

Less that one month before the 1918 Armistice, she was sold to the Belgian company Lloyd Royal Belge, renamed Péruvier (oh the irony) and converted into a coal freighter that shuttled coal from the UK to Brazil for a couple years, frequently suffering severe breakdowns of her absolutely ancient engines. on June 1st, 1920, it was discovered that one of her coal bunkers was now a raging inferno, one which took almost 3 weeks to finally put out.

at this point it was clear that Péruvier was going nowhere under her own power ever again. After a few rounds of towing to various ports, she eventually arrived at the shipbreakers in Vlissingen, Netherlands on March 4th, 1923.

|

|

Thus ended Dupuy de Lôme. the first modern Armored Cruiser of the Steam-and-Steel era, yet obsolete and practically forgotten after less than a decade of lightning fast advancement.

GENERAL CHARACTERISTICS:

Displacement:

6,201 long tons (normal loads)

6,576 long tons (fully loaded)

Length:

111 meter at waterline

114 meters overall

Beam:

15.7 meters

Draft:

7.07 meters (normal load)

7.49 meters (fully loaded)

Powerplant:

13 Amirauté cylindrical fire-tube boilers of highly questionable performance fed the engines… speaking of which-

bizarrely the engines weren’t all in a vertical format, despite vertical mountings being firmly established late in the ironclad-era as the preferable setup to maximize floor space since machinery rooms were largely now all underwater anyways:

1 Vertical Triple Expansion Steam Engine producing power delivered to the central shaft powering the central 4.4 meter diameter propeller

2 Horizontal Triple Expansion Steam Engines each producing power delivered to their corresponding shafts powering two 4.2 meter diameter propellers

This odd and somewhat subpar powerplant produced 13,005 indicated horsepower (13,186 metric horsepower) that gave a maximum speed of 19.73 knots (36.54 km/h; 22.70 mph), just under the estimated speeds of 20 knots.

Fuel:

1,060 tons of coal

Range:

4,000 nautical miles (7,400 km; 4,600 mi) at a speed of 12.5 knots (23.2 km/h; 14.4 mph)

BONUS FACTOID: Metacentric height: 0.695 meters above the waterline

this gave the ship a long slow roll that made her an uncertain gunnery platform, likely because the short ranges and firing rate of the main guns at the time made long rolls very unhelpful- this is why bilge keels were added in 1897, greatly limiting her roll and making far more stable as she still had a very slow roll.

crew: 521, likely around a couple dozen officers and the rest being regular enlisted seamen.

ARMOR:

the armor itself is nickel steel (the origin of what’s today called Stainless Steel) made by the great steel manufacturer Le Creusot… in the years before Pre-WWI French dominance in steel manufacturing, and before the advent of Harveyized Nickel Steel and Krupp Steels.

to point out how limited in tensile strength even steel alloys are without special heat treating, nickel steel is only marginally more durable than Mild (AKA Constructional) Steel, with nickel steel having a figure of merit of 0.67 compared to mild steel’s 0.60… still… far, far lighter than wrought iron, and far better still than compound armor though.

middle cross section, showing the armor belt, armored weather deck, and below water protective deck

Armor Belt: 100mm all over

the primary armor of the ship wasn’t so much a long strip as it was a giant bathtub, from the bottom edge of the protective deck 1.38 meters below the waterline, right up to the quarterdeck to encapsulate the vast majority of the ship in 100mm of nickel-steel armor. and never thinning along its span.

Protective Decks:

the protective deck was 30mms thick, being a 20mm top plate of high-strength steel, backed by a 10mm bottom plate of mild steel joining the bottom edges of the belt 1.38 meters below the waterline, and rising to the waterline at the middle of its span to form the turtleback.

immediately below this main turtleback deck was an additional 8mm splinter deck, with the open space between the two filled with coal for a minor extra increase of protection.

along this whole length of protection as well as up to 1 meter above the waterline was an internal cofferdam that was mainly to slightly aid buoyancy.

Internal Protection:

below the protective decks were 13 transverse (horizontal) watertight bulkheads, and above the turtleback were 3 more.

Conning tower: 100mm on the front

the conning tower (the half-cylinder room above and behind the bow gun on the photos above) was a tiny 1.5 meter half-cylinder box with 100 mm of armor only at the front. it was unarmored on the side, floor, roof, or the open back.

Gun turrets: 100mm all around

both the 194mm and 164mm gun turrets had 100mm protection all around.

ARMAMENT:

2×1 – 194mm (7.6 in) Modèle 1887 guns in single mounts on each side amidships https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Canon_de_194_mm_modèle_1887 - note, 2 shots per minute AKA 30 second reload

http://www.navweaps.com/Weapons/WNFR_76-45_m1887.php

the Mle 1887 guns and their mountings are a particularly strange mix of old and new.

as cruiser-grade armament of most eras largely follow capital ship armament development in miniature and with more limits; whether they be technological or financial; the 194mm Mle 1887 were in single mounts as was common prior to 1900, while conversely due to the 2-year head start on smokeless powder development that France had, they just took a 194mm Mle 1883 and greatly extended its barrel to a length of L/45 caliber- totally unheard of prior to the 1890s outside of monsters like the 100-ton gun.

strangely, these main guns were mounted amidships on each side as seen above really making them more of the secondary battery. They had a elevation capability of -5 to +15 degrees, and had about 80 degrees of travel in either direction.

with that said, being the first is usually accompanied by being near enough the worst when compared to later developments- and being made in the early 1890s with all the limitations of the era, the fire rate was a poor 2 RPM at best… and there’s a strange reason as stated by Navweaps:

"Unusually, the shell and powder magazines were located two sections away from the turret stalk which meant that ammunition needed to move horizontally, presumably by overhead rails, to the gunhouse. "

so the ammunition magazine was literally just placed too far away to achieve an average fire rate… neat.

|

|

speaking of ammunition, here we get to another quirk of the vintage of the armament (though it has no ingame effect). the 3 main gun shell types used throughout Dupuy de Lôme’s lifetime were: CI, APC, and the rarely seen SAPC.

the latter two are self explanatory- Armor Piercing Capped and Semi-Armor Piercing Capped.

CI… means Cast Iron. uhhh yeah. sure.

initially the Cast Iron shell was the only 194mm shell type carried, however by roughly 1897 it was quickly phased entirely out for shells that weren’t a total joke, only carrying APC and SAPC afterwards.

|

|

APC: a 90.3 kg shell, 52.4 cm long, with a muzzle velocity of 770 m/s and still at 619 m/s at 2000 meters downrange, carrying a 1.59 kg Mélinite bursting charge, to a maximum range of 11,500 meters from a firing elevation of 14.2 degrees

SAPC: a 89.5 kg shell, 59.0 cm long, with a muzzle velocity of 770 m/s and still at 619 m/s at 2000 meters downrange, carrying a 4.33 kg Mélinite bursting charge, to a maximum range of 11,500 meters from a firing elevation of 14.2 degrees

|

|

|

6×1 – 164mm (6.5 in) Modèle 1887 guns in single mounts on the bow and stern Canon de 164 mm modèle 1887 — Wikipédia note, 3 shots per minute AKA 20 second reload

France 164.7 mm/45 (6.5") Models 1891, 1893, 1893-1896 and 1893-1896M - NavWeaps

while the main guns are slightly undersized compared to the international standard at 7.6-inch, the secondary caliber is slightly oversized at 164.7mm (6.5-inch).

and the development arc of the 164mm guns quite closely follows the 194mm guns: 45-caliber super extendo barrel, single mount, CI/APC/SAPC shells (and the iron shell again was quickly dropped), and the unusual placement of having the secondary guns in leading positions, with a 164 per end placed where every other ship of every other nation would have its main guns in the commanding fore and aft positions on the weather deck and ye olde-style superfiring over the side guns off to either side a deck level lower.

the fire rate wasn’t egregious though, at 3 RPM aka 20 second reload. while poor by WWII standards, that’s not bad for an enclosed turret mount in 1895.

elevation was about -10 to +25 degrees, and the side guns had about 80 degrees of travel in either direction while the leading guns had about a 300 degree traverse arc, unconstrained until it slammed into the superstructure behind it

APC: 121.0 lbs. (54.9 kg), 43.5 cm long, , with a muzzle velocity of 770 m/s, carrying a 970 gram Mélinite bursting charge, to a maximum range of 15,400 meters from a firing elevation of degrees

SAPC: 115.3 lbs. (52.3 kg), 48.5 cm long, with a muzzle velocity of 770 m/s, carrying a 3.1 kg Mélinite bursting charge, to a maximum range of 18,000 meters

at this point you may notice that in oh so french fashion, the secondary guns have far longer maximum range than the primary guns. But this is just elevation limits and historically was barely noticed outside of the Courbet-class Dreadnoughts- going into the 1890s the French thought average sustained naval combat ranges would only be around a maximum of 2 kilometers… AKA literally unchanged from the Napoleonic-era. that this range was tripled in active combat just a decade after Dupuy de Lôme entered service shows just how impactful naval rangefinders and fire control were.

|

|

4×1 – 65mm L/50 Mle 1888/1891 “9-Pounder” guns

http://www.navweaps.com/Weapons/WNFR_26-50_m1888.php

this rarely seen caliber was like most French bore sizes, a holdover from the age of sail. From its inception with the original Mle 1888, this caliber was meant specifically to be the next incremental step up from the instantly successful Hotchkiss QF 6-pounder, going from a 57mm 6-pound shell, to a 65mm 9-pound shell.

muzzle velocity was 715 m/s, and the mount was actually an high angle/low angle mount for taking potshots at torpedo boats at long range, which 20 years later retroactively makes it a psuedo-AA gun

|

|

10×1 47mm/40 QF 3-Pounder Hotchkiss guns

as seen ingame on IJN Kurama- the Hotchkiss 3-Pounder by this point was nearly a global mainstay for its weight class, and just about everybody used them with no changes even when locally manufactured.

|

|

4×1 – 37mm/20 M1885 1-Pounder Hotchkiss (Early)

USA 1-pdr. (0.45 kg) [1.46" (37 mm)] Marks 1 through 15 - NavWeaps - Navweaps lumps these in in its USN section, because the US Navy apparently used every 37mm made by man, and the Hotchkiss 1-pounder in both its L/20 and L/27 barrels are both labeled as: “Hotchkiss Light, Short, Mark 1”

This is the original, original L/20 caliber version of the 37mm semi-automatic action single barrel Hotchkiss- and is not to be confused for either the revolver cannon of the same name, or the slightly later L/27 caliber version. these and other 1-pounders were produced en masse during their brief heyday as the definitive hail-of-fire anti-torpedo boat weapon.

|

|

4×1 – 450mm (17.7 in) Torpille 450 Mle 1892 torpedo tubes in underwater tubes

as expected for a ship of this vintage, the French used 18-inch Whitehead-derived torpedoes like everybody else.

the Mle 1892 was the third automobile torpedo (prior to the self-propelled torpedo, what we now call Mines were called torpedoes) in French service, and was more or less the proof of concept for the 18-inch torpedo in Marine Nationale service, as the the previous 15-inch and 14-inch Mle 1877 one-offs clearly didn’t work out.

the Mle 1892 had a 75 kg guncotton warhead and like all 1st gen torpedoes has a range of…

…useless at best.

though at least there were two settings:

the faster setting had a laughable 400 meter range at 31 knots… just in case all the gunners were literally blind

and the slow setting was 800 meters at 28 knots… probably for use in the event of an early 1870s ironclad glaring from across the table.

SOURCES:

online:

70077 - French Armored Cruiser Dupuy-de-Lome, 1895, 1/700 - this model kit is a 1/700 scale model kit from Combrig Models, and includes a slideshow of the EXTREMELY detailed construction process including every bit and greeble that comes with a faithful recreation. it’s kind of amazing honestly

http://www.navypedia.org/ships/france/fr_cr_dupuy_de_lome.htm

http://le.fantasque.free.fr/php/ship.php?page_code=dupuy#weapon

literary:

Chesneau, Roger & Kolesnik, Eugene M., eds. (1979). Conway’s All the World’s Fighting Ships 1860–1905. Greenwich: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 0-8317-0302-4.

Feron, Luc (2011). “The Cruiser Dupuy-de-Lôme”. In Jordan, John. Warship 2011. London: Conway. ISBN 978-1-84486-133-0.

Silverstone, Paul H. (1984). Directory of the World’s Capital Ships. New York: Hippocrene Books. ISBN 0-88254-979-0.